Ethan Peebles

The Church of the East, also referred to as the Apostolic Church of the East, first emerged in the fifth century, although it traces itself to Apostolic times as the church spoken of in the New Testament. It developed primarily in the Sasanian Empire, rival of the Roman Empire, speaking not Latin or Greek, but Syriac, and in this respect is notably different from the imperial Orthodox Churches.1 It is in the context of schisms between Greek speaking churches, often tied up in the milieu of Roman-Persian political hostilities, that the Church of the East was wrongly labeled “Nestorian,” an appellation often found in dated studies.2 The Islamic conquest of Persia and the proselytizing zeal of the church of the east encouraged its spread through Turkish and later Sogdian lands, with these Christians moving east from Merv via the silk road. The movement of Christian groups into Sogdian territory, the geographic and economic bridge between Turkish lands and China, occurred between the fifth and eight centuries, although a lack of literary sources makes reconstruction of this dispersion difficult to reconstruct.3 There are however abundant archeological traces of Christian material presence along the silk roads dating from this period (Fig. 1).4 Linguistic and fragmentary literary evidence demonstrates that this period saw hybridization along the silk road, from Merv to Turfan, of the Church of the East with that of Manichaean, Mazdean, and Zoroastrian traditions.5 It is evident that the Church of the East from early on was willing and active in the adoption of indigenous belief and customs, with these adaptations affecting the presentation of Jesus.6 Manichaean texts established the precedence of using Buddhist epithets to describe Jesus, such as “Buddha of Harmony” (hefo 和佛), “Tathāgata” (rulai 如來), and “King of the Dharma” (fawang 法王).7 More Orthodox leaning Christians in the Turfan Oasis, the traditional “gateway to China,” left behind texts in various languages using similar Buddhist terminology.8

Figure 1 (Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 18)

It is unclear when exactly Christians of the Church of the East actually entered China.9 By the beginning of the Tang dynasty (618-907), sufficient Eurasian trade lanes had connected Europe with China, and these avenues continued to proliferate.10 It is probable that Christianity in some form or another had entered China prior to the Tang dynasty, although this cannot be certain. Some Chinese Christians would go so far as to trace their presence to the first century Apostle Thomas, an almost certainly legendary tradition.11 We do know that by the time of the Tang dynasty, missionaries of the Church of the East had adopted Chinese, and by 781 had begun to refer to their faith as Jingjiao 景教, meaning “luminous teaching.”12 Our best source for a definitive narrative would be the Xi’an stele, a inscribed limestone stele, featuring both Chinese and Syriac scripts, found in Xi’an China and erected in the aftermath of the devastating An Lushan Rebellion (755-763).13 The stele reports that the monk Aluoben brought Jingjiao to the Duke Fang Xuanling of Chang’an in 635, and there it was given imperial license and advanced relatively unperturbed for the next century and a half. Besides a short historical overview of the success of Jingjiao in China, the stele also provides an outline of the faith.

Jesus is presented as the “Luminous Honored Messiah (Mishihe 弥施訶)” and a distinct person of the “Three-One (Wo sanyi fenshen 我三一分身).” He fashioned the universe in accordance with a markedly Daoist cosmology.14 According to the stele, using the same term for of Confucian sages,15 the “Holy One (sheng 聖)” came down to establish the “Ineffable New Teaching”- including the typically Christian beatitudes (“eight conditions”), theological virtues (“three constant virtues”), canonical scriptures, baptism, and anti-diabolic soteriology. These concepts, moreover, are all expressed in Confucian terminology, echoing traditional and familiar Chinese concepts.16 The stele includes a lengthy encomiastic poem, establishing Jesus as a sustainer of order, whose honor and blessing is bestowed upon good emperors. He thus takes on not a purely theological or soteriological role, but a social one. The Tang emperor is sustained by this foreign deity, not on account of official imperial endorsement, but of imperial sanction. The stele speaks in regard of the Tang throne,

The sacred sun spread its crystalline rays around it,

and the favorable wind swept away the darkness.

Renewed blessings descended upon the royal house,

and the omens of calamity vanished forever.17

Although the emperor need not be Christian, his tolerance of Jingjiao is sufficient for divine blessing, unlike western counterparts wherein the imperial blessing depended not only on total endorsement, but also total endorsement of particular Christological strictures. Followers of Jingjiao in China were conscious of their minority position despite high theologically motivated aspirations. Deeg in fact argues that Chinese Christians saw themselves as an imperiled diaspora as opposed to a zealously proselytizing group, in this way demonstrating why there is little Christian influence on surrounding religions despite heavy counter-influence on their own.18 Their insularity, enshrined in particular Christian bureaucratic systems,19 in an overwhelmingly non-Christian China then was essential to their identity. The intensity of their missionary self-presentation and their impact on other traditions are disputed points.20 This issue is tied up also in the extent of the preservation of their Syriac heritage; scholars such as Nicolini tend to emphasize their especially Chinese elements (typically linguistic or rhetorical), while more conservative scholars such as Ferreira would emphasize the retained Syriac elements (typically doctrinal) of Jingjiao.21

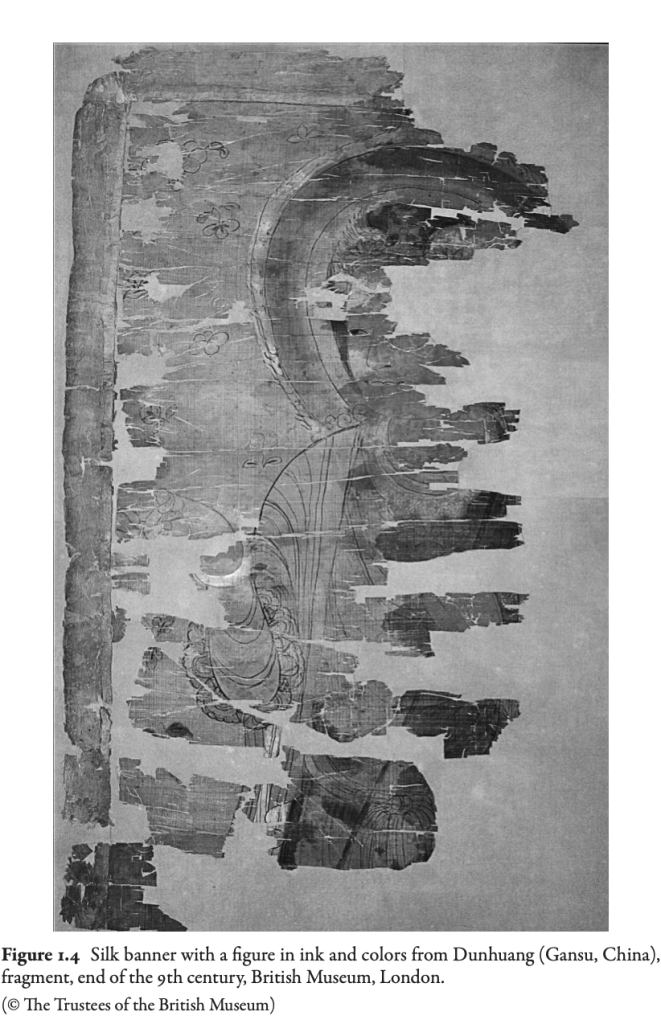

Beside a rich textual tradition, early Chinese Christians were, being far from the iconoclastic controversies gripping their Roman and Syrian counterparts, highly visual.22 The Xi’an stele records: “Aluoben, of the kingdom of Da Qin (the Eastern Roman Empire), came from far away to present scriptures and images in our supreme capital.”23 Our greatest examples of Jingjiao art comes from the remarkable discoveries at Dunhuang, a major stop linking northern and southern routes at the eastern end of the silk road (Fig. 1). Christians maintained a sustained presence there from the eighth to eleventh centuries, including a monastic community.24 Besides numerous texts from a swathe of religious traditions-all found in material proximity-, Dunhuang also provides our best preserved Chinese depictions of Jesus. These pieces are our most powerful indication of Christian adoption of Chinese imagery. Most interesting in content is one Tang silk hanging found in Dunhuang, depicting Jesus Christ in a manner heavily resembling Buddhist art, save for clear Christian imagery, especially the crucifix used to identify the piece (Fig. 2, 3). Jesus is depicted not as a rabbi, but a Buddha. Another striking piece is an icon depicting Palm Sunday found in Turfan (Fig. 4). The characters depicted are far removed from their Palestinian historical scene, but here are seen in distinct Chinese dress and style.

Figure 2 (Nicolini Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 25)

Figure 3 (Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 24)

Figure 4 (Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 23)

Notes

- Baum, Wilhelm, and Dietmar W Winkler. The Church of the East : A Concise History.

(London; Routledge, 2003), Ch. 1. ↩︎ - Brock, Sebastian P, “The Christology of the Church of the East,” Religions 15, no. 4 (2024),

457. ↩︎ - Hansen, Valerie, “The Synthesis Of The Tang Dynasty: The Culmination of China’s Contacts

and Communication with Eurasia, 310-755,” in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late

Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250-750, ed. Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael

Maas (Cambridge, 2018), 108–22; Nicolini-Zani, Matteo, The Luminous Way to the

East: Texts and History of the First Encounter of Christianity with China, trans. William

Skudlarek (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2022), 13. ↩︎ - Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 19. All images taken from The Luminous Way to the East. ↩︎

- Traditions cited in the 9/23/24 lecture. ↩︎

- Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 47-50. ↩︎

- Ibid., 51. ↩︎

- Ibid., 52. ↩︎

- See Ferreira, Johan, “Tang Christianity: Its Syriac Origins and Character,” Jian Dao, 21 (2004): 129–57. ↩︎

- Hansen, “The Synthesis Of The Tang Dynasty.” ↩︎

- Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 71. ↩︎

- Ibid., 60. ↩︎

- Ibid., 120. ↩︎

- Ibid., 198 note 6. ↩︎

- For example, see Analects 9.6 in Philip J. Ivanhoe and Bryan W. Van Norden, Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. (Seven Bridges Press, 2001), 25, in which the term “endowment” of a sage coincides with Christian understanding. ↩︎

- Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 202. ↩︎

- Ibid., 215. ↩︎

- Deeg, Max, “The Christian Communities in Tang China: Between Adaptation and Religious

Self-Identity,” in Buddhism in Central Asia III: Impacts of Non-Buddhist Influences, Doctrines,

ed. Carmen Meinert, Henrik H. Sørensen, and Yukiyo Kasai (Brill, 2023), 124. ↩︎ - Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 85. A bureaucratic imaginary was right at home in Chinese religion, as argued by Wolf; Arthur P. Wolf, “Gods, Ghosts, and Ancestors,” in

Studies in Chinese Society, ed. Arthur P. Wolf (Stanford University Press, 1978), 131-182. ↩︎ - Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, xiv. ↩︎

- See Ferreira, “Tang Christianity.” ↩︎

- Parry, Ken, “The Art of the Church of the East in China,” in Jingjiao: The Church of the East in

China and Central Asia, ed. Roman Malek (Routledge, 2006), 321. ↩︎ - Nicolini-Zani, The Luminous Way to the East, 205. Emphasis mine. ↩︎

- Ibid., 8, 113. ↩︎

Bibliography

Baum, Wilhelm, and Dietmar W Winkler. The Church of the East : A Concise History. Routledge, 2003.

Brock, Sebastian P. “The Christology of the Church of the East.” Religions 15, no. 4 (2024): 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040457.

de Bary, Theodore and Richard Lufrano, eds. “Chinese Responses to Early Christian Contacts.” In Sources of Chinese Tradition, volume II: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press, 2000.

Deeg, Max. “The Christian Communities in Tang China: Between Adaptation and Religious Self-Identity.” In Buddhism in Central Asia III: Impacts of Non-Buddhist Influences, Doctrines, ed. Carmen Meinert, Henrik H. Sørensen, Yukiyo Kasai, 123–44. Brill, 2023.

Ferreira, Johan. “Tang Christianity: Its Syriac Origins and Character.” Jian Dao 21 (2004): 129–57.

Hansen, Valerie. “The Synthesis Of The Tang Dynasty: The Culmination of China’s Contacts and Communication with Eurasia, 310-755.” In Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250-750, ed. Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael Maas, 108–22. Cambridge, 2018.

Ivanhoe, Philip J., and Bryan W. Van Norden. Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. New York: Seven Bridges Press, 2001.

Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. The Luminous Way to the East: Texts and History of the First Encounter of Christianity with China. Translated by William Skudlarek. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Parry, Ken. “The Art of the Church of the East in China.” In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia, ed. Roman Malek, 321–39. Routledge, 2006.

Wolf, Arthur P. “Gods, Ghosts, and Ancestors.” In Studies in Chinese Society, ed. Arthur P. Wolf, 131-182. Stanford University Press, 1978.